Emerging analysis from the investigation into GB gas and electricity supply by the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) suggests that consumers are paying more than they need to because of their failure to “engage in” the market and because of shortcomings in the regulation of the sector.

Some seven months into an investigation instigated by Ofgem and six months after producing its initial issues statement setting out the areas on which it would be focusing, the CMA has published an updated version of the issues statement and a summary of smaller suppliers’ views on barriers to entry and expansion in the market (one of a series of “working papers” that provide more detail of the CMA’s analysis and the evidence on which it is based).

The problem

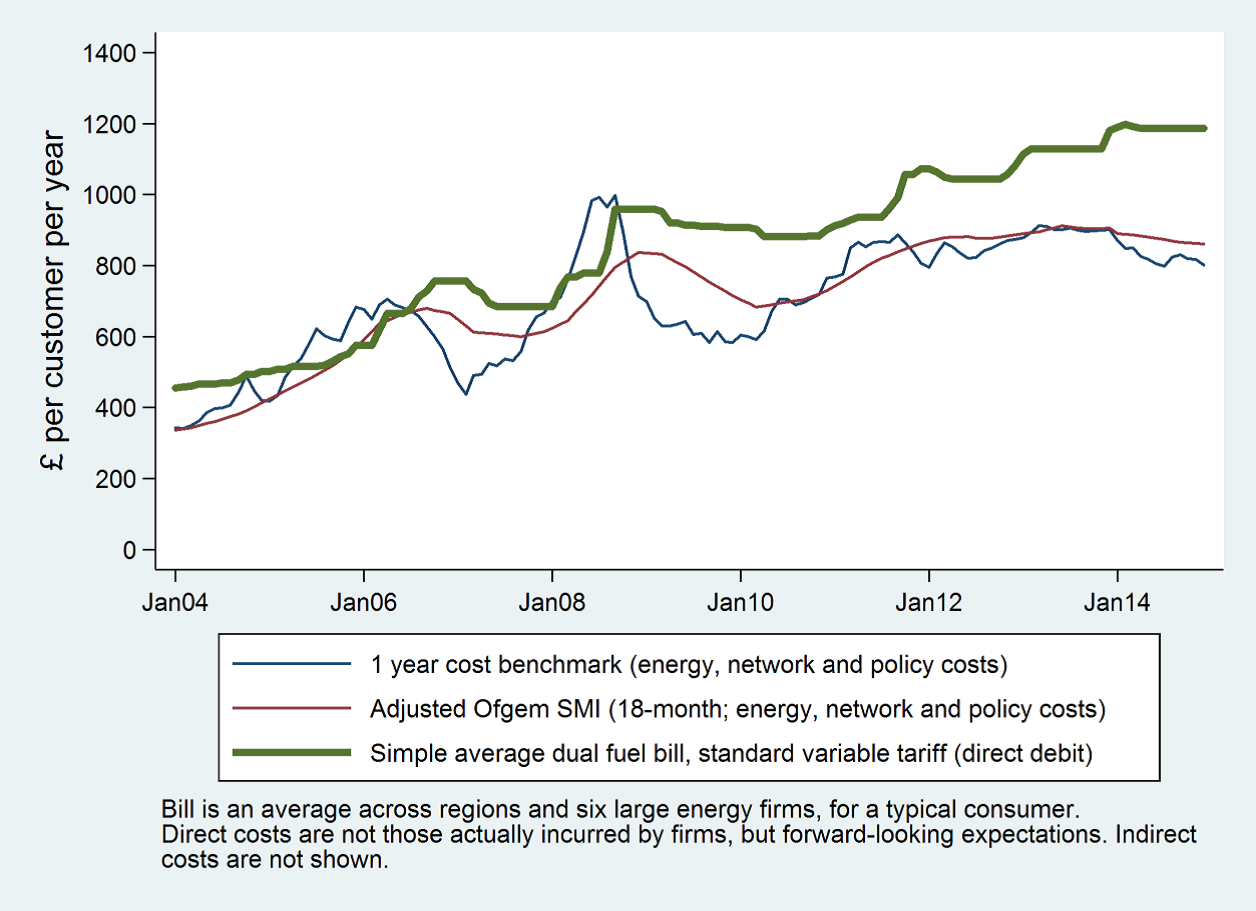

The CMA is fairly clear that both domestic and “microbusiness” consumers of gas and electricity are paying more than they need to – noting, for example, that “95% of the dual fuel customers” of the Big 6 could have saved an average of between £158 and £234 by switching tariff and/or supplier. They also note, as others have done before them, that customers on “Standard Variable Tariffs” (SVT) tend to see their bills rising faster and falling slower than increases and decreases in the underlying costs of supply would suggest (the so-called “rocket and feather” effect – see graph below).

The search for causes

However, the CMA has so far rejected a number of the “usual suspects” when it comes to explaining why consumers appear to be paying more than they need to, without there being any obvious reason for their loyalty to their existing suppliers. The initial issues statement was based on four hypothetical “theories of harm” that could account for failures of competition:

- “market power in electricity generation leads to higher prices;

- opaque prices and/or low levels of liquidity in wholesale electricity markets create barriers to entry in retail and generation, perverse incentives for generators and/or other inefficiencies in market functioning;

- vertically integrated electricity companies harm the competitive position of non-integrated firms to the detriment of the customer, either by increasing the costs of non-integrated energy suppliers or reducing the sales of non-integrated generating companies;

- energy suppliers face weak incentives to compete on price and non-price factors in retail markets, due in particular to inactive customers, supplier behaviour and/or regulatory interventions.”.

Taking each of these in turn, the CMA’s current (but explicitly provisional) analysis is as follows:

- The Big 6 are not making excessive profits from generation and do not have the ability or incentive – individually or collectively – to increase profits by withdrawing capacity.

- There are not significant problems as regards the transparency of the wholesale markets. Those smaller suppliers who complain about a lack of liquidity, at least for certain products, have yet to persuade the CMA that this is a major concern, although they note that Ofgem’s Secure and Promote licence condition has not addressed all the problems in this area.

- The CMA also does not think that the Big 6’s vertical integration enables them to cause independent generators to restrict their output or allows them to take action in the wholesale markets that disadvantages independent retailers. One independent supplier saw vertical integration as a competitive disadvantage (potentially tying a supplier to generating plant whose efficiency reduces over time, especially if measured against the best in the market).

- The only one of the original “theories of harm” which seems to offer an explanation of the failure of competition is the fourth one above, notably “inactive consumers”. Although the domestic market share of independent suppliers grew from 1% to 7% (electricity) or 8% (gas) between July 2011 and July 2014, the fact remains that almost half of domestic consumers have not switched supplier for at least 10 years. Many do not even believe switching is possible. As one of the independent suppliers points out, having a large base of relatively price-insensitive customers on SVT may enable an incumbent to compete more aggressively against new entrants for the business of those who do take active steps to get a good deal. Another suggests that it is almost as if there are two markets: one composed of potential switchers and another of those who are terminally loyal to their incumbent supplier.

Regulation may be stifling competition

One of the things that stands out in the CMA’s analysis is the emphasis on the potentially adverse effects that various aspects of sectoral regulation may be having on competition. This is most conspicuous in the addition of two new hypothetical “theories or harm”:

- “the market rules and regulatory framework distort competition and lead to inefficiencies in wholesale electricity markets;

- the broader regulatory framework, including the current system of code governance, acts as a barrier to pro-competitive innovation and change.”.

But it is also seen elsewhere. Examples of potentially problematic regulation identified include:

- Elements in Ofgem’s recent reform of cashout prices (the Electricity Balancing Significant Code Review) “may lead to an overcompensation of generators”.

- It may be inefficient not to have a system of locational prices for constraints and losses on the transmission network. It may be that consumers in Scotland and the North of England should be paying more, and those in the South of England paying less, for their electricity.

- The Capacity Market element of Electricity Market Reform (EMR) “appears broadly competitive”, but the CMA plan to look at if further. They note that the Contracts for Difference regime may not secure the lowest prices for renewable generation subsidies by having separate “pots” for different technologies, rather than requiring them to compete all-against-all, or by allowing the award of contracts on a non-competitive basis, before observing, equally obviously, that “there are potentially competing objectives that need to be taken into account in the design of the CfD allocation mechanism”. One independent supplier also characterises the system by which CfD costs are recovered from suppliers as “madness”.

- But any problems caused by EMR are for the future. Looking back, the CMA have clearly listened both to those who have criticised Ofgem’s 2009 decision to prohibit regional price discrimination (while providing exemptions for promotional tariffs), which may have led to a consumer-confusing increase in the number of tariffs, and to those who question Ofgem’s 2013 decision to force suppliers to “simplify” their tariff portfolios drastically, which resulted in the loss of tariff discount options that may or may not have been valued by consumers. However, the CMA have yet to form a final view on the merits of either decision.

- It has often been observed that the 250,000 account threshold, above which suppliers become subject to the Energy Company Obligation (ECO), may act as a barrier to growth for independent suppliers. More interestingly, the CMA note that the costs of the social and environmental policies delivered by suppliers “fall disproportionately on electricity rather than gas”, meaning that “domestic consumption of electricity attracts a much higher implicit carbon price than domestic consumption of gas” – which may have implications for the take-up of electrical heating systems (normally thought of as part of decarbonising energy usage). This is another area where the CMA will be investigating further.

- Finally, the CMA identify aspects of the Balancing and Settlement Code (BSC) and other industry agreements that could be standing in the way of more effective competition. They ask, for example, why, once smart meters have been rolled out, there are no plans to move away from the system whereby domestic customers’ consumption is “profiled”, rather than being based on half-hourly meter readings. Failure to take advantage of the new technology in this way could “distort incentives to innovate”. The CMA will also be considering further whether there are just too many codes in the electricity industry (constituting a barrier to entry) and whether the mechanisms for changing industry rules may be stacked too heavily in favour of incumbents and the status quo. On the first point, Elexon itself, administrator of the BSC, apparently thinks that “rationalising” the codes will remove potential barriers to competition.

Next steps

Interested parties have until 18 March 2015 to comment on the updated issues statement. The next major step will be the publication of “provisional findings”, currently scheduled for May 2015. Overall, the investigation is not due to conclude before November / December 2015, and it could be extended into 2016. It is of course far too early to speculate on possible remedies, but for now the more obviously Draconian options in the CMA’s armoury, such as the breaking up of vertically integrated groups, appear unlikely outcomes. Something eye-catching to cause “inactive” consumers to “engage”, and a lot of “boring but important” changes in the regulatory undergrowth around industry codes and agreements seem reasonable bets for now, but there is a long way to go yet.